History Timeline

We invite you to take a fascinating look back at the Authority’s early history, conception and realization.

Ninth Ward

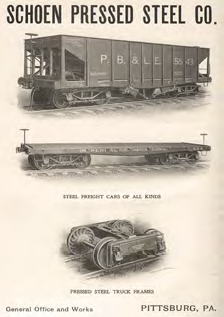

With the addition of the Schoen Manufacturing Company, the area continued to grow as a booming industrial center through the 1920s.

Read more

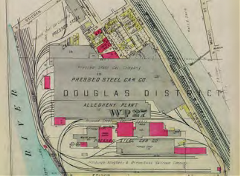

Charles T. Schoen came to Pittsburgh in 1890, enlisting the assistance of Henry W. Oliver in establishing interest for his patented pressed steel railroad car design. Schoen established the Schoen Manufacturing Company on Cass Street, fabricating freight car parts from pressed steel as a substitute for more commonly used cast iron. On March 26, 1897, he was awarded a contract to build 600 pressed steel cars for the Pittsburgh, Bessemer and Lake Erie Railroad, filling the order in just nine months while completing a $500,000 plant expansion.

With demand exploding, Schoen purchased the Allegheny mills of Oliver Iron and Steel and later built an even larger facility in McKees Rocks. On January 12, 1899, Schoen merged with the Fox Pressed Steel Company and reincorporated as the Pressed Steel Car Company. Schoen was forced out in 1901, and by 1909, working conditions at the McKees Rocks plant had deteriorated to a point that the facility was known as the "Slaughterhouse." Workers went out on strike in July, and a series of bloody confrontations climaxed on August 22, with reports varying between 12 and 23 dead.

By the early 1920s, the Allegheny and McKees Rocks facilities were churning out 45,000 freight cars and more than 750 passenger cars annually. Demand for new rail cars soon ebbed, however, and by World War II, the company was facing the likelihood of failure. Wartime production of Sherman M-4 tanks served as a temporary lifeline, but by the mid-1950s the Pressed Steel plants were closed and the properties sold as warehouse space.

Pork House

The first identity of ALCOSAN’s current location belonged to the Pork House, which started as a public house and whiskey still that expanded over the years to accommodate freight interests and new industry resulting from the Civil War.

Read moreHugh Davis, an Irish immigrant, purchased land extending from the river bank to the present site of Riverview Park and divided the bottoms of “Davisville” equally among his children. Hugh Davis, who was later first treasurer of Allegheny City, built a stone public house and whiskey still on his property, but it was the addition of William B. Holmes’ Whirlpool Pork House that would earn the locale its new identity. In her book, "Old Penn Street", Agnes M. Hays Gormly recalled an 1823 wedding journey to Sewickley passing “Outer Depot, Pork House, Jack’s Run and Kilbuck” by carriage. Later references to Pork House Row, Pork House Landing and the Pork House mills were evident into the 20th century.

In 1851, regular passenger service commenced from Allegheny to New Brighton, 27 miles down the Ohio River. The line would later become part of the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne and Chicago line, leaving Pork House ideally positioned as a freight hub between the rails and the river and garnering the attention of the region’s growing industrial concerns.

Originally part of Pine Township and later the southern boundary of Ross Township, this area, adjacent to the City of Allegheny and running south of the new railroad to Jack's Run, was absorbed into McClure Township in 1858. On March 28, 1870, it was incorporated as the Ninth Ward of Allegheny, and on December 7, 1907, was included in the annexation by the City of Pittsburgh.

The coming of the Civil War in 1861 spurred massive industrialization in northern cities. Pork House expanded with the construction of the Ardesco Oil Refinery in 1862. Located along what is now Tracy Street in the vicinity of ALCOSAN’s employee parking area, the Ardesco Refinery was the scene of a tremendous explosion on August 18, 1866. The blast, caused by the use of weak iron in a newly-installed refining still, resulted in the destruction of Ardesco’s still house, receiving house, barreling and carpenter shops, 10,000 empty barrels, 1,000 barrels of crude and 1,500 barrels of refined oil.

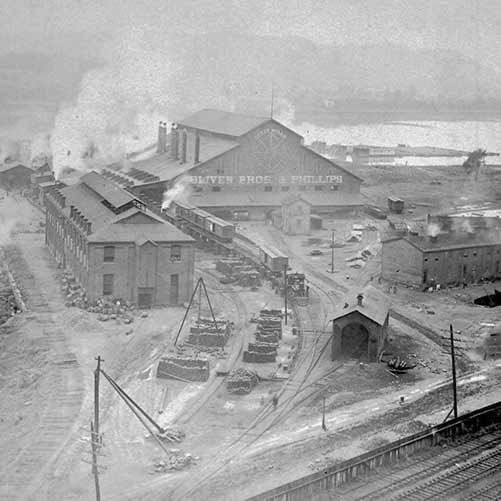

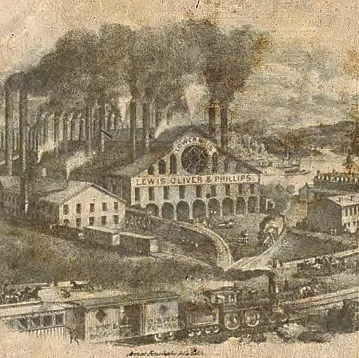

On April 25, 1863, Henry W. Oliver, William J. Lewis and John Phillips entered into the manufacture of carriage bolts, nuts, washers and wagon thimble skeins under the name of Lewis, Oliver and Phillips. The company completed construction of the Excelsior Iron and Bolt Works at Birmingham (South Side) in 1864, and the lower mills of the Allegheny Works, located in the vicinity of what is now the ALCOSAN primary treatment facilities, in 1866. On August 6, 1880, the firm reorganized as Oliver Bros. and Phillips, and soon thereafter became one of the largest manufacturers of iron bar in the United States. The business, which incorporated as Oliver Iron and Steel Co. on November 9, 1887, sold its lower rolling mills to the Schoen Pressed Steel Co. in 1897 and the rest of the works to the railroad car manufacturer in 1899.

Verner Junction

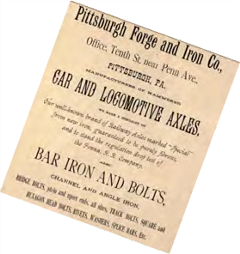

James Verner purchased land near the Pork House mills in 1864 for his Pittsburgh Forge and Iron Company. He developed a “company town” on the property, and the area, including a nearby railroad station came to be known as Verner Station.

Read moreJames Verner also purchased land adjacent to the Pork House mills of Lewis, Oliver & Phillips in 1864 and organized the Pittsburgh Forge and Iron Company specializing in the manufacture of hammered car and locomotive axles. Verner also laid out a “company” town on the property, designing a street and housing plan for the predominantly foreign workforce. The area, including a nearby railroad station, became known as Verner Station and encompassed the entirety of ALCOSAN’s treatment plant site.

Born in Monongahela City in 1818, Verner lived most of his early life in the Fourth Ward of Pittsburgh. He was educated at Allegheny College in Meadville and, upon completion of the Allegheny Valley Railroad, laid out a village on that line also called Verner Station and later Verona. In 1841, he married Anna Murry and returned to Pittsburgh, becoming a partner in a brewing firm and later obtaining a charter for the Citizens Passenger Railways Company. In 1859, the first horse-drawn street railway west of the Alleghenies began operating between Penn Avenue and 34th Street.

Born in Monongahela City in 1818, Verner lived most of his early life in the Fourth Ward of Pittsburgh. He was educated at Allegheny College in Meadville and, upon completion of the Allegheny Valley Railroad, laid out a village on that line also called Verner Station and later Verona. In 1841, he married Anna Murry and returned to Pittsburgh, becoming a partner in a brewing firm and later obtaining a charter for the Citizens Passenger Railways Company. In 1859, the first horse-drawn street railway west of the Alleghenies began operating between Penn Avenue and 34th Street.

With the organization of Pittsburgh Forge and Iron (below), Verner became the firm’s first president, serving for four years and remaining on the company’s directors for many subsequent years. During this time, expansion of the railroads and the manufacture of heavier rail cars increased both the demand for car axles and the need for labor in the Pork House mills.

In great numbers, newly arriving immigrants - Italians, Poles and Slavs - joined the Germans, English and Welsh as rollers, puddlers and laborers in the iron works and quickly overwhelmed the tenements of Verner and Woods Run. Over-crowding in the densely populated neighborhoods spawned squalor and disease. By 1899, the Department of Charities suggested “adopting immediate measures to check the epidemic of typhoid that now reigns by exterminating the 50 or more filth holes that infest lower Allegheny.” Two-thirds of typhoid cases were foreigners living in small houses occupied by 15 to 60 boarders.

Decisions & Designs

With ALCOSAN’s incorporation in 1946, the Authority began sampling to determine the extent of the region’s sewage problems, and planning for the regional wastewater treatment plant began.

Read more By mid-year of 1946, the Authority began conducting underground audits and weir sampling to determine the extent of the region’s sewage problems. Included in these audits were previously unknown mileage, capacities and conditions of the county’s 102 municipal sewer systems. Thirty-five different sewer locations were chosen in preliminary sampling, which included the participation of 59 municipalities and 15 industrial sites.

By mid-year of 1946, the Authority began conducting underground audits and weir sampling to determine the extent of the region’s sewage problems. Included in these audits were previously unknown mileage, capacities and conditions of the county’s 102 municipal sewer systems. Thirty-five different sewer locations were chosen in preliminary sampling, which included the participation of 59 municipalities and 15 industrial sites.

Planning efforts continued through the first half of 1947, and by September 24, the Authority submitted to the Army Corps of Engineers a plan to lay interceptor sewers in the Youghiogheny, Monongahela, Allegheny and Ohio rivers.

The Authority completed preliminary sampling on November 1, 1947. In all, an average flow of 65 million gallons per day from a population of about 678,000 was measured, sampled and analyzed to determine the character of wastes emanating from municipal and industrial sewers.

The Authority completed preliminary sampling on November 1, 1947. In all, an average flow of 65 million gallons per day from a population of about 678,000 was measured, sampled and analyzed to determine the character of wastes emanating from municipal and industrial sewers.

On February 9, 1948, the Authority released the first of five reports recommending an $82 million single-plant treatment system for Pittsburgh and the surrounding communities. The report suggested the 48.1-acre Verner tract on the north side of the Ohio River, opposite McKees Rocks, as an appropriate location to site the treatment plant. The planned collection system included 91 miles of main interceptor sewers and 65 miles of branch interceptor sewers for immediate construction.

On March 1, 1948, consulting engineers Metcalf & Eddy approved the single-plant treatment plan, and on June 2, Mr. Laboon announced formal approval by the state Sanitary Water Board. This cleared the way for the Authority to prepare and issue contractual agreements to participating municipalities and industries.

In October, the County Board of Commissioners adopted a resolution extending the Authority’s powers to include acquisition of water works. On April 12, 1949, the Borough of Pitcairn became the first municipality to return a signed long-term contract for inclusion in the Authority’s treatment plan. Only Mt. Lebanon, Ben Avon and Tarentum would follow. As a result of the disappointing return, the Authority negotiated an alternative with the city titled “Project Z” that dropped 63 communities and lowered the overall cost to $42 million.

By June of 1950, the Authority began preliminary core bores in the area of the treatment plant site. The bores indicated a variety of underground conditions including river silt, ash, coal screenings, sand and building foundations remaining from the Pork House and Verner days.

In September, the Authority completed construction of a pilot plant located under the Homestead High-Level Bridge. Built to emulate a fully designed facility and test selected treatment methods, the pilot plant cost $14,000 and had the capacity to treat up to 100,000 gallons of sewage per day.

Devastation

The rivers provided factory owners convenient access to materials necessary to keep their factories going. However, the rivers became lifeless streams of disposal causing a need for an emphasis on the environment.

Read moreThe industrialization of this area played a common yet integral role in Pittsburgh’s early rise as the world’s workshop. By staging their industries along the region’s rivers, men like Verner, Schoen, Carnegie and Frick ensured convenient access to coal and other materials necessary to keep their factories and profits in motion. Rivers were viewed not as natural resources, but as arteries to deliver natural resources. As a result, little concern was afforded when waterways, once teeming with life, became lifeless streams of disposal for those same factories.

In the 1920s, smoke billowing from factories blackened the mid-day sky and coated the city in 165.8 tons of particulate matter per square mile each month, equal to the weight of 100 cars. In mill areas, as much as 600 tons of soot and cinders rained on homes and businesses in a month’s time. In addition, municipal and industrial waste, mine drainage, and other pollutants led to poor water quality and the spread of disease.

In 1907, Pittsburgh began sand filtration and chlorination of water supplies, and the typhoid rates began to drop. At the same time, the city and hundreds of upstream communities continued to dump untreated sewage and industrial waste into the rivers. By the mid 1940s, less than 2 percent of the discharges into the Ohio River received any treatment at all, and the Monongahela, void of aquatic life, ran red with acid mine drainage, mill effluent, and other pollutants.

The election of Cornelius D. Scully as mayor in 1936 put a new emphasis on the environmental problems facing the City of Pittsburgh and the region. Scully was pressured by the newspapers to act in reversing the damage that years of industrial prosperity wreaked upon the condition of the city. He created the Commission for the Elimination of Smoke, opened new parks and concentrated on programs to provide the city with a cleaner water supply. With the coming of war in 1941, however, Scully was forced to put aside his campaign as the city’s factories refitted to supply the war machine. The region produced 95 million tons of steel, 52 million shells and 11 million bombs to supply the Allied effort, but the pollution that resulted turned rivers into cesspools and the day sky into night.

Renaissance

After World War II, agencies in Allegheny County began to take action to address the environmental challenges that resulted from the industrial boom. The Allegheny Conference on Community Development led the charge to establish a regional sanitation district.

Read moreAs the war neared an end, civic leaders once again took up reversing years of environmental destruction in the region. Richard King Mellon, president of the Pittsburgh Regional Planning Association, generated support for a postwar planning committee to serve as a coordinating mechanism for regional transportation and environmental improvement efforts. The Allegheny Conference on Community Development was thus incorporated in 1944. Forming a partnership with newly elected mayor David L. Lawrence, Mellon used the Allegheny Conference as a vehicle to promote what would be known as the Pittsburgh Renaissance, a “growth coalition” of capital, labor and politics. The immediate goals of this powerful partnership included smoke abatement, flood control, renewal of the Golden Triangle business district and the establishment of a regional sanitation district.

In May of 1945, two developments would move the county closer to addressing water quality issues: the Pennsylvania Municipal Authorities Act of 1945 passed on May 2, and enforcement of the 1937 PA Clean Streams Act.

The PA Municipal Authorities Act provided for the incorporation of bodies with power to acquire, hold, construct, improve, maintain and operate, own and lease property to be devoted to public uses and revenues. These uses included transportation, bridges, tunnels, airports, sewer systems and sewage treatment works.

On May 17, Pennsylvania’s Sanitary Water Board began enforcing the PA Clean Streams Act by ordering 102 municipalities and 90 industries in Allegheny County to prepare preliminary plans and specifications for sewage treatment. The board further ordered cessation of sewage and industrial discharges by May 1947.

Breaking Ground

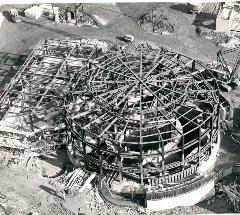

Plans and specifications for the treatment plant were developed, and the official ground breaking took place on April 4, 1956.

Read moreThe Authority proceeded with planning for construction of the treatment plant and collection system, hiring Celli-Flynn of McKeesport as consulting architects for all Authority buildings and Michael Baker, Jr. Inc. of Rochester to make soundings for eight interceptor river crossings.

In August of 1953, consulting engineers Metcalf & Eddy reported that plans and specifications for the treatment plant were complete. The state Sanitary Water Board finally approved the Authority’s plan for an $87 million treatment system and 63 miles of intercepting sewers on June 24, 1954, ordering the system to be constructed and operational by June 30, 1958. Following public hearings in November, a permit application was submitted for approval by the Corps of Engineers.

On February 15, 1955, the Authority received City of Pittsburgh Ordinance No. 40, expressing the city’s desire to become a member of the Authority. The request was approved by the Authority on February 17, adding three city-appointed members to a reorganized executive board and naming Edmund S. Ruffin, Jr. as new chairman. With the original members set to resign on March 1, John F. Laboon was appointed executive director and chief engineer.

On August 22, 1955, the commissioners formally approved the sale of a portion of the plant site owned by the city and the Board of Education for $250,000. The remainder of the property was later acquired from Jones & Laughlin Corp. for $890,000. On October 4, 1955, the Authority executed a $100 million loan through trustee Mellon National Bank & Trust to finance construction. Provided at an interest rate of 2.25%, the loan was considered interim financing until conditions were favorable for the issue of long-term revenue bonds.

Beginning December 6, 1955, bids for the first construction contracts were received by the Authority. In all, $50 million worth of contract bids were opened through the month of December. In addition, all 343 property owners involved in required rights-of-way were contacted by year’s end, with 26 properties expected to require condemnation proceedings. On March 1, 1956, contractors began the first stages in the construction of the Authority’s wastewater treatment system.

Construction

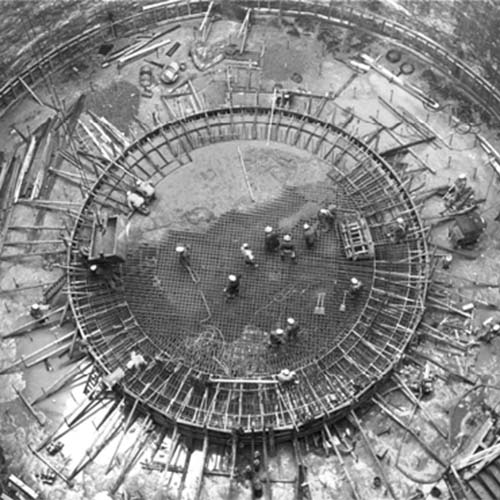

The enormous task of construction of the treatment plant and the interceptor sewer system took more than three years and required hundreds of workers.

Read moreAs groundbreaking ceremonies were being conducted, contractors from Dravo were beginning reparatory work for the construction of the main interceptor arteries. Workers began constructing concrete access shafts at 36th Street opposite Herr’s Island and at Belmont Street just upstream of the West End Bridge. The work involved installing a cofferdam at the upstream end near Washington Boulevard, with tunnel boring progressing downstream.

On July 1, a strike by steelworkers delayed shipment of structural steel to the site by nearly a month. Additional stoppages during construction included:

- June 22-26, 1956

Dispute between cement finishers & carpenters over setting expansion material

- September 17-18, 1956

Plumbers refuse to lay pipe in trenches dug by heavy or building construction laborers

- June 3-9, 1957

Plumbers strike for increase in wage scale

- June 10, 1957

Ironworkers strike over Wayne Crouse, Inc. millwrights moving screw conveyors

- September 3-9, 1957

Dispute between carpenters and electricians

- January 15-21, 1958

Equipment operators strike over a discharged master mechanic

- May 29-July 22, 1958

Lathers strike for an increase in wage scale; Plasterers idle due to strike

- September 1-13, 1958

Slowdown by electricians, reason unknown

- April 5-15, 1959

Work stoppage of all trades, reason unknown

The accumulated delay resulting from labor strikes, slowdowns and boycotts during construction of the plant was more than 72 days.

In February of 1957, Executive Director Laboon concluded that the dead weight of the main pump station as designed was insufficient to keep the entire structure from floating under the hydraulic pressure produced under certain operating conditions. Holes were drilled into the bottom rock of the excavation and heavy reinforcing bars were used to anchor the concrete floor of the pump station. The cost of the change was approximately $73,000.

In February of 1957, Executive Director Laboon concluded that the dead weight of the main pump station as designed was insufficient to keep the entire structure from floating under the hydraulic pressure produced under certain operating conditions. Holes were drilled into the bottom rock of the excavation and heavy reinforcing bars were used to anchor the concrete floor of the pump station. The cost of the change was approximately $73,000.

In April of 1957. the Dravo Corporation completed construction of the river wall at the plant site, the first contract to be completed under the Authority plan. Surplus excavation materials from the treatment plant site were disposed of less than one mile away in the vicinity of Benton Avenue. Now the site of the John Merry athletic fields, the area was originally planned for the disposal of incinerator ash once the plant became operational.

In April of 1957. the Dravo Corporation completed construction of the river wall at the plant site, the first contract to be completed under the Authority plan. Surplus excavation materials from the treatment plant site were disposed of less than one mile away in the vicinity of Benton Avenue. Now the site of the John Merry athletic fields, the area was originally planned for the disposal of incinerator ash once the plant became operational.

Dedication

The ALCOSAN system began operation in April 1959, and the treatment plant was formally dedicated on October 1, 1959. Engineers overcame several initial operational difficulties, and in January 1960, the Authority was nominated for the “Outstanding Civil Engineering Achievement Award” by the American Society of Civil Engineers.

Read more March 20, 1958, Authority employees voted unanimously to unionize, forming the Local 433 of the Utility Workers Union of America (UWUA). Speaking to a public hearing on May 14, 1958, regarding the discharge of wastes in the sewer system, Executive Director John F. Laboon stated that the Allegheny River would be a fishable water again within six months of the system going into operation.

March 20, 1958, Authority employees voted unanimously to unionize, forming the Local 433 of the Utility Workers Union of America (UWUA). Speaking to a public hearing on May 14, 1958, regarding the discharge of wastes in the sewer system, Executive Director John F. Laboon stated that the Allegheny River would be a fishable water again within six months of the system going into operation. Construction of the treatment facilities continued through the winter of 1958 and into the spring of 1959. On April 30, bulkheads were removed from individual outfall connections and the system was put into operation as a primary treatment plant.

An initial rate schedule went into effect on June 1, 1959. Based on water usage and billed quarterly, charges were $0.30 per 1,000 gallons (100,000 gallons or less), with a minimum charge of $2.50 per quarter and $0.50 per quarter for disposals.

Initial operational difficulties included the formation of football-sized grease balls in the sewers. It was estimated that by June of 1959, four to five tons of grease had been removed from the system and trucked to the City of Pittsburgh’s incinerator before an engineered solution could be found. In addition, community complaints regarding odors emanating from the Authority’s chimney became so prevalent that, by October, the Board of Directors ordered a general shutdown of the plant’s four incinerators pending an engineering study.

Remnants of Hurricane Gracie forced the October 1, 1959, dedication of the wastewater treatment plant indoors. Referring to an investigation by Pennsylvania State Senator Frank Kopriver, Jr. into the Authority’s rates and expenditures, then Governor David L. Lawrence launched into a heated attack on “politicians who capriciously - I might say - maliciously attack such programs.” Kopriver was mayor of the City of Duquesne in 1954 and vehemently opposed that city’s participation in the Authority’s plan.

Remnants of Hurricane Gracie forced the October 1, 1959, dedication of the wastewater treatment plant indoors. Referring to an investigation by Pennsylvania State Senator Frank Kopriver, Jr. into the Authority’s rates and expenditures, then Governor David L. Lawrence launched into a heated attack on “politicians who capriciously - I might say - maliciously attack such programs.” Kopriver was mayor of the City of Duquesne in 1954 and vehemently opposed that city’s participation in the Authority’s plan. Results of Kopriver’s investigative committee failed to support his premise that the Authority’s work progressed “slowly in an inefficient and careless manner with resulting excessive expenditures and waste.” Conversely, the Republican majority stated that, “with some minor exceptions, the Authority is to be commended, and particularly Mr. Laboon for acquiring top quality construction of sewers and plant, and there is no evidence of extravagance or waste.”

Results of Kopriver’s investigative committee failed to support his premise that the Authority’s work progressed “slowly in an inefficient and careless manner with resulting excessive expenditures and waste.” Conversely, the Republican majority stated that, “with some minor exceptions, the Authority is to be commended, and particularly Mr. Laboon for acquiring top quality construction of sewers and plant, and there is no evidence of extravagance or waste.”On January 1, 1960, the Authority was nominated for the ”Outstanding Civil Engineering Achievement Award” by the American Society of Civil Engineers. The recognition served as a fitting punctuation for the successful planning, design, construction and initial operation of ALCOSAN’s collection and treatment system, and would set an indicative tone for the Authority’s progression and expansion into the future.